Antoni Porowski, Queer Eye’s food expert, is no stranger to a thirst trap on Instagram, regularly posting shirtless photos and even scoring an underwear ad campaign. But in a recent interview, he opened up about how he has struggled with his body image, especially in relation to other gay men.

“I was most comfortable with my body when I was in a relationship with women,” he told Glamour. “There wasn’t a sense of comparison because we were different. It was my first relationship with a guy where I looked at myself and I was like, ‘Oh my biceps aren’t as big as his, I wish my legs were longer, I wish my torso was longer.’ I got really self-conscious and it was the comparison.”

Antoni’s remarks struck a chord with me when I read the interview, and it turns out, I wasn’t alone. Gay and bisexual men are reportedly significantly more likely than heterosexual men to develop an eating disorder, with an “inability to meet body image ideals within some LGBTQ+ cultural contexts” cited as a key factor in research by NEDA.

“It’s not just Instagram, the apps, etc., but it’s real life too,” says Matt, 28. “I go to club nights where everyone is shirtless and it’s intimidating. I don’t feel comfortable taking my shirt off, because the bodies are incredible, exactly like on Instagram, and I can’t even compare.”

Even guys who are confident with high self-esteem aren’t immune to the idea that they are being held to exacting standards, and found wanting. “I like to think I’m decently conventionally attractive,” says Luke, 27. “Like I have a lot going for me, but there’s a constant background feeling of not being sexy enough.”

What, then, is sexy enough?

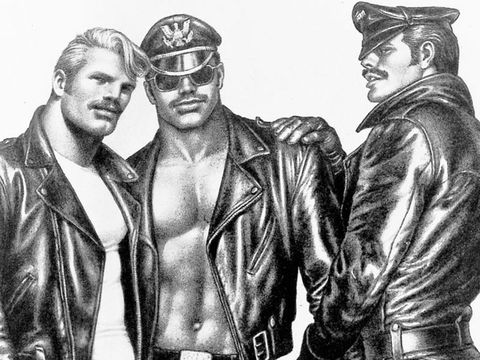

A lot has been said about how gay male culture is “sexualized,” but that isn’t by accident. The aesthetics of nude, muscular, masculine-presenting bodies, popularized by the artist Tom of Finland, were embraced and adopted by gay men in the ’70s as a means of asserting their own identity when their only representation in media at the time was a small range of fey stereotypes. Durk Dehner, President of the Tom of Finland Foundation, said in 2014: “It was part of his imagery that made those young boys grow up to be healthy and strong in their self-attitudes, and that was really a fundamental part of gay liberation.”

Tom of Finland

Later on, having muscles was also a way for gay men to outwardly perform their beefy, blooming health to the world during the AIDS crisis. This defiance of stereotypes enabled gay men to see themselves in a stronger light than how the media portrayed them. But what began as a proud assertion of identity has itself become a trope; the stereotype of a gay man now is one who goes to the gym and takes care of himself.

As Antoni points out, same-sex desire invites a degree of comparison, but it also includes an element of aspiration, with men being attracted to somebody because they wish they could look or act more like him. Conversely, a guy might seek out a partner who has the kind of traits he has cultivated in himself (the boyfriend twin meme exists for a reason).

I personally find myself avoiding messaging men on Grindr whose profiles show defined abs or bulging biceps, because while I like my own body, somewhere along the way I’ve internalized the idea that gay men prefer somebody who matches their own body type. This isn’t always true, of course, but the mindset does help to create self-delineating “levels” of hotness, with muscular, “straight-acting” (usually white) men at the top.

And if there’s one thing white men are historically good at, it’s gatekeeping. “No fats, no femmes, no Asians” is such a common refrain on Grindr that it’s become a point of parody, with one guy even selling T-shirts bearing the slogan (although it was unclear whether the message of his merch satirized or endorsed that viewpoint).

The men who espouse this kind of racist body-shaming are being rightfully called out in the broader discourse. Filmmaker Jamal Lewis channeled personal experience of body discrimination into a documentary entitled No Fats, No Femmes, while Grindr has encouraged its users to be “kinder” in their language to each other. But these dating profiles don’t exist in a vacuum; they are informed by a physique-centric gay scene, and a society that rewards whiteness and old-fashioned ideas of masculinity.

Now that a greater plurality of voices, identities and body types is starting to be represented in queer media, a newer set of norms are emerging: LGBTQ+ people of all body types and ethnicities are advocating for self-love and body positivity on social media and demonstrating that having muscles isn’t the only way to be sexy.

Hopefully this will continue, and a greater variety of beautiful bodies will become incorporated into queer culture, so that the younger generation who are currently exploring their own sexuality or gender identity will face fewer rigid definitions of what it means to be worthy of desire.

Source: Read Full Article