A study led by David Berry and Alessandra Riva from the Center for Microbiology and Environmental Systems Science (CeMESS) at the University of Vienna has significantly advanced our understanding of prebiotics in nutrition and gut health.

The study, published today in Nature Communications, reveals the extensive and diverse effects of inulin, a widely used prebiotic, on the human gut microbiome. The scientists view their method as a pioneering step towards personalized dietary supplements.

In recent years, prebiotics like inulin have increasingly captured the attention of the food and supplement industry. Prebiotics are non-digestible food components that promote the growth of beneficial microorganisms in the gut. Inulin, one of the most popular commercial prebiotics, is naturally abundant in foods such as bananas, wheat, onions, and garlic. When we consume these foods, inulin reaches our large intestine, where it is broken down and fermented by gut bacteria.

Studies have shown that inulin may have positive effects on human health, such as anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer properties. However, the complex nature of the human gut, home to about 100 trillion microbes, poses a challenge in deciphering the exact effects of supplements like inulin.

Innovative approach to track the impact of inulin

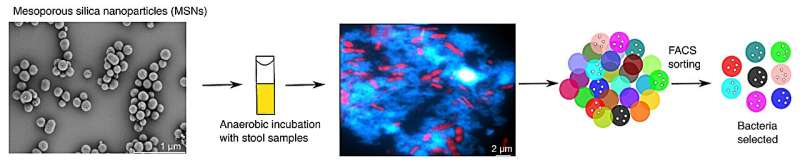

In a recent study led by researchers at the University of Vienna, fluorescence-labeled nanoparticles were used to track the interaction of inulin with gut bacteria. These inulin-grafted nanoparticles, when incubated with human stool samples, yielded a surprising result: a wide range of gut bacteria, far more than previously assumed, can bind to inulin.

“Most prebiotic compounds are selectively utilized by only a few types of microbes,” explains David Berry, the lead researcher. “But actually, we found that the ability to bind to inulin is really widespread in our gut microbiota.” Using a state-of-the-art technique to identify cells actively synthesizing proteins, the team discovered that a diverse group of bacteria actively responds to inulin, including some species not previously associated with this capability, such as members of the Coriobacteriia class.

“Inulin supplements have been on the market for years, but precise scientific evidence of their health-promoting effects has been lacking,” says Berry. “We used to think that inulin mainly stimulates Bifidobacteria, the so-called ‘good bacteria,’ but now we know that the effect of inulin is much more complex. Our study is a trailblazer for the future of microbiome-based medicine: with our method, dietary supplements can be personalized, precisely designed, and scientifically substantiated in the future.”

Every person’s microbiota reacts differently to prebiotics

“Interestingly, when comparing stool samples from different individuals, we noticed significant differences in the microbial communities that respond to inulin,” says Alessandra Riva, also a leader of the study. “These findings highlight the importance of considering individual differences in the development of dietary recommendations and microbiome-based interventions,” she explains.

The CeMESS research not only contributes to a better understanding of prebiotic metabolism in the human digestive tract but also to a better framework for its investigation. “Our approach to marking and sorting cells based on their metabolic activity is relatively new,” says Riva. “We hope that our study can serve as a framework for future research and the development of new microbiome-based therapies.”

More information:

Alessandra Riva et al, Identification of inulin-responsive bacteria in the gut microbiota via multi-modal activity-based sorting, Nature Communications (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-43448-z

Journal information:

Nature Communications

Source: Read Full Article