New research from the University of Hertfordshire has underscored the disparities in mental health support for adults with kidney disease, recommending specialist, culturally-adapted approaches for South Asian patients who face barriers in accessing mental health screening and care.

Data shows that up to one in three patients with kidney disease will experience depression at some point. Those who require hospital-based hemodialysis—the most common form of dialysis for people with advanced kidney disease—are particularly vulnerable to low mood or symptoms of depression, given the nuances of the treatment itself as well as its impact on sustaining everyday life activities.

People of South Asian origin are between three and five times more likely to develop end-stage kidney disease: this group comprises around 5% of the U.K. population, but 12.2% of kidney service users. Despite this, patients from these cultural groups are rarely included in mental health research.

Researchers at the University of Hertfordshire—who have long championed inclusive research at the intersection of kidney care and mental health—have now conducted a first-of-its-kind study to address this disparity, undertaking assessments with over 200 South Asian dialysis patients and analyzing the results to make a number of specialist recommendations.

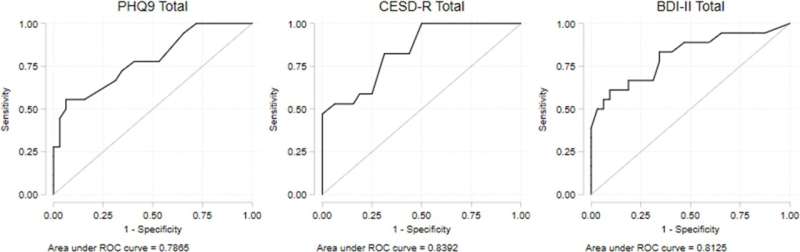

The paper, “The use of culturally adapted and translated depression screening questionnaires with South Asian haemodialysis patients in England,” published this week in PLOS ONE, highlights the barriers that prevent South Asian patients being effectively screened for symptoms of depression, and the steps that should be taken to identify relevant symptom experiences.

Dr. Shivani Sharma, Associate Professor in Health Inequalities at the University’s School of Life and Medical Sciences, co-led the new study with Professor Ken Farrington, Consultant Nephrologist at the Lister Hospital, East and North Hertfordshire NHS Trust. Dr. Sharma explains, “Our study unveiled a number of obstacles to identifying depression in South Asian kidney patients. Language and cultural barriers were a common theme—for example, in many South Asian languages, there are no equivalent terms for depression. Where English is a language barrier, even when family members are on hand to translate, these cultural differences in how patients experience and express their symptoms contribute to under-diagnosis.”

To overcome these challenges in their study, Dr. Sharma and her team not only provided culturally adapted and translated questionnaires in Gujarati, Punjabi, Urdu and Bengali, but also recruited bilingual project staff who became crucial to the study, as only 18% of patients were able to self-complete the study unassisted. This demonstrates that personalized, culturally sensitive support can have a major impact on people’s ability to engage meaningfully with screening and support. By doing so, the researchers achieved a 97% consent to research completion rate, which is exceptionally promising to address under-representation in kidney research more generally—a key national priority.

Dr. Sharma continued, “I am very proud of this study, which represents a significant step forward in improving access to inclusive care for patients managing multiple disadvantages. We have highlighted that we need to re-imagine what culturally responsive mental health care looks like, and how it is enabled in the context of living with a long-term condition.”

More information:

Shivani Sharma et al, The use of culturally adapted and translated depression screening questionnaires with South Asian haemodialysis patients in England, PLOS ONE (2023). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0284090

Journal information:

PLoS ONE

Source: Read Full Article