Cholera, an infection that causes severe diarrhea and can be deadly, is once more spreading in several low-income countries. In its latest update on the disease, the World Health Organization (WHO) noted that the global situation has further deteriorated in recent months.

The 24 countries currently reporting outbreaks are spread across Africa, the Caribbean, and south Asia. Since WHO’s December 2022 report new cholera outbreaks have been reported in Burundi, South Africa and the Dominican Republic. Cases are also now being reported from north-west Syria, in areas not under Syrian government control.

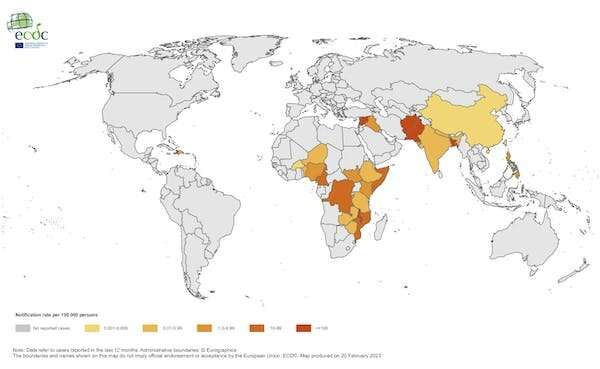

Geographical distribution of cholera cases reported worldwide, February 2022 to February 2023

African countries reported 26,000 cases and 660 deaths in the first four weeks of this year compared to nearly 80,000 cases and 1,863 deaths during the whole of 2022.

When we look at global infections, cases reported to the WHO up to mid March number almost 339,000 resulting in 3,287 deaths. For most countries represented, these figures include cases and deaths only for 2023, though for some countries they include cases and deaths from all or part of 2022 as well.

While this makes quantifying increases difficult, global cases in recent months appear to be significantly higher compared with previous years.

And the true numbers are likely to be much greater as under-reporting is a known problem for cholera. A large proportion of cases are not diagnosed and some countries may be reluctant to report that they are experiencing a cholera outbreak.

Symptoms, treatment and prevention

Cholera causes watery diarrhea that can be so profuse that the stool loses its brown coloring, giving the diarrhea a characteristic “rice water” appearance. Death, when it occurs, can be very rapid, within a few hours after the onset of symptoms. It’s usually due to dehydration or electrolyte imbalance.

Cholera affects children more frequently than adults and if affected, children are also more likely to die. Children who are malnourished are at greater risk of severe disease and death from cholera.

Notably, some countries are reporting particularly high death rates during this surge. From 2000 to 2010 the global case fatality rate varied between 2% to 3%, but since then it gradually fell to a low of 0.2% in 2019. Across all African countries the case fatality rate is now 2.2% and over 3% in Malawi, Nigeria and Tanzania.

Deteriorating food security in many countries, especially in Africa, could be driving this increased mortality rate.

In terms of treatment, the top priority is to rehydrate patients either using an oral rehydration salt solution, or in more serious cases, with an intravenous solution. Antibiotics may shorten the duration of the diarrhea and can be given in people who are more severely ill.

The are several cholera vaccines available and more in development. The vaccines in current use are given orally. Estimates of the vaccines’ effectiveness vary somewhere between 65% and 85%. Vaccination doesn’t give lifelong protection—booster doses are needed every two years.

From history to the modern day

Cholera was historically centered around the Ganges delta in India. But it spread from there in a series of global pandemics, the first one starting in 1817. These pandemics were responsible for millions of deaths around the world, including in Europe.

The current and seventh pandemic started in 1961 and is now the longest lasting cholera pandemic in history. It has caused several waves of infection.

The main risks for cholera are usually linked to poor hygiene, poor sanitation and contaminated drinking water. Most infections are due to the consumption of contaminated food and drinking water. Transmission directly from one person to another is uncommon.

Why the current surge?

The WHO has identified the main drivers behind this cholera surge to include extreme weather events such as cyclones, flooding and drought, along with humanitarian crises, conflict and political instability. They’ve also cited inadequate supplies of cholera vaccines and added pressures on health services due to, among other things, the COVID pandemic.

Indeed, cholera is one of the diseases likely to become more common under climate change, largely as a result of its effects on water and sanitation through more frequent floods and droughts. Outbreaks of cholera often follow major natural disasters such as earthquakes, as experienced by Haiti in 2010, and floods, as in Bangladesh in 1998.

Wars can also trigger cholera epidemics as seen in Yemen from 2016. Similarly, following the break-up of the Soviet Union there was a large epidemic of cholera across countries that were previously member states.

Cholera so often follows wars and natural disasters largely because of the damage to water and sanitation infrastructure leading to contamination of drinking water. People may also be displaced during wars or after disasters and be be forced to live in temporary housing with inadequate water and sanitation. Food insecurity also follows such disasters, which we know increases the risk of severe cholera.

Assessing the risk in Europe

If case numbers continue to increase or even continue at current levels we will likely see more cases globally this year than at any time in the past three decades.

Case numbers were very high in 2017 and 2019 but almost all of these cases were in war-torn Yemen. Now cases are increasing on multiple continents.

Cholera only really spreads when water and sanitation infrastructure fails, and this is a very marginal risk in high-income countries. At present the main risk for Europeans will be for travelers to areas where epidemics are occurring.

For anybody traveling to a country with local transmission of cholera, it would be wise to seek advice on whether vaccination may be appropriate. Regardless, it’s important to follow strict food and water hygiene practices when in a cholera-affected country.

The nearest countries with cholera epidemics are Lebanon and north-west Syria. These border on Turkey, which has just suffered a major earthquake.

Further, war is continuing in Ukraine and more than one million people in the country no longer have access to running water. So we cannot afford to be complacent about the risk of cholera in Europe.

Provided by

The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source: Read Full Article