The loss of smell or taste for COVID-19 survivors who experience those symptoms frequently leads to depression, a loss of appetite and a decreased enjoyment of life, according to an ongoing Virginia Commonwealth University study.

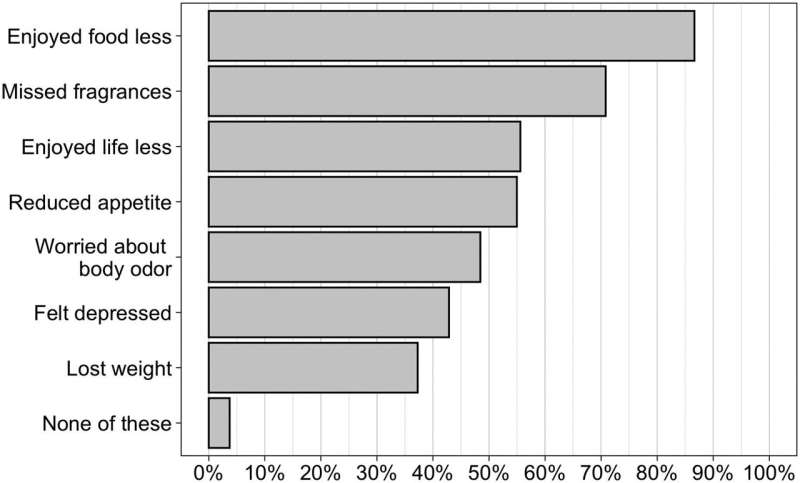

In the study of quality of life and safety for those with loss of smell or taste related to COVID-19, 43% of participants reported feeling depressed.

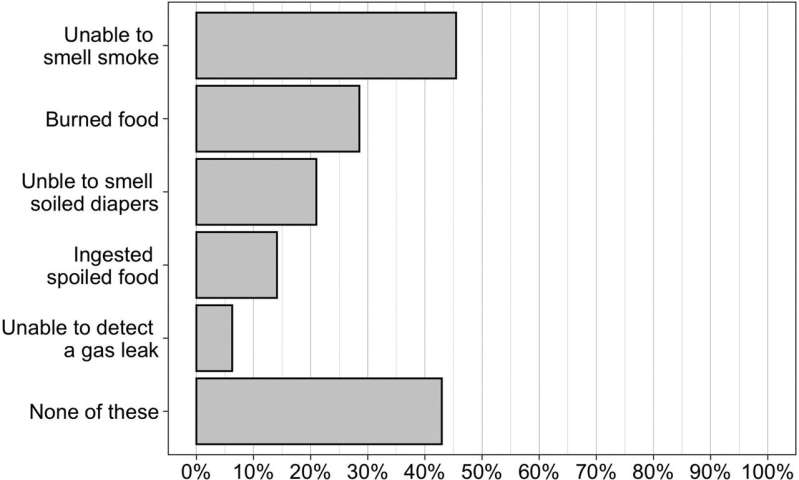

Of the 322 respondents to the ongoing COVID-19 smell and taste loss survey who had tested positive for COVID-19 and reported a loss of smell or taste, 56% reported decreased enjoyment of life in general while experiencing their loss of smell or taste. The most common quality-of-life concern was reduced enjoyment of food, with 87% of respondents indicating it was an issue. An inability to smell smoke was the most common safety risk, reported by 45% of those surveyed.

Evan Reiter, M.D., medical director of the Smell and Taste Disorders Center at VCU Health and a member of the VCU research team that created the survey, says the health and safety concerns stemming from these responses give insights into the larger picture of the long-term health impacts of COVID-19.

“People who have had smell or taste loss are exposed to these risks of having personal safety events, depression or reduced quality of life,” Reiter said, “so it’s important for their health care providers to have real discussions with people about what they can or should do to compensate for their loss, whether it’s short term or long term. The hope is that they can avoid some of these patient safety issues or nutritional issues due to food aversions.”

The Smell and Taste Disorders Center’s researchers Daniel Coelho, M.D., lead author and a professor in the Department of Otolaryngology —Head and Neck Surgery at the VCU School of Medicine; Richard Costanzo, Ph.D., senior author, the center’s research director and professor emeritus in the Department of Physiology and Biophysics; Zachary Kons, a third-year medical student at VCU; and Reiter launched the longitudinal survey in April 2020 to learn more about how long COVID-19-related smell or taste loss might last. To date, more than 2,600 people nationwide have participated in the survey, which tracks symptoms over time. The group shared their findings in a paper published this spring in the American Journal of Otolaryngology online ahead of print.

In addition to new data on the impact of loss of smell and taste, the study shares potential considerations for those interested in options to recover their smell or taste.

“Unfortunately for patients with persistent olfactory deficits, no definitive treatments exist to effectively restore function,” the authors wrote. “A number of treatments have been explored specifically for post-viral olfactory dysfunction; however, current evidence only supports a potential benefit of olfactory training therapy.”

Also called smell training, olfactory training therapy is an option that Reiter said is “very low risk, low cost and basically just involves smelling some selected essential oils,” he said, with clove, eucalyptus, rose and lemongrass often being the recommended scents. The Clinical Olfactory Working Group, a group of physicians worldwide with a strong research interest in the sense of smell, recommended the method as an option early this year.

“I can’t say the proof is perfect, but they’ve shown in different ways that people who do smell training may have a higher likelihood of recovering from a post-viral olfactory loss,” Reiter said.

While the majority of COVID-19 survivors’ sense of smell and taste improves or returns within one or two months, those who lose their sense of smell for longer than two months—approximately 33% or more, according to the group’s previous research—may experience problems even if it comes back. Data from the center’s study shows that over 45% of respondents indicated alterations in odor perception.

“These people reported what we call parosmias—so they smell their hamburger and it smells like cat litter or they smell a milkshake and it smells like gasoline. That kind of distortion is really big in contributing to at least the loss of appreciation of food and even, in some people, leading to food aversions,” Reiter said. “People lose their sense of smell altogether, but then as it comes back, it comes back in with this distortion so it’s that double-edged sword.”

Respondents also reported loss of appetite (55%) and weight loss (37%) as a result of loss of taste or smell. Reiter said some strategies may help deter malnourishment.

“Trying to find different combinations of spices to appeal to your intact taste buds, since your sense of smell isn’t giving you that information, could continue to allow the food to be palatable. In some cases, just appealing to the other senses through different textures of foods or different colors of food can help so everything doesn’t look the same and also taste very bland,” he said. “As small as it may seem, it may decrease that deficit just a bit.”

And, Reiter said, there are safety precautions people can take if they’ve lost their sense of smell or taste.

“There are simple things that oftentimes go neglected when we’re taking our sense of smell for granted: Making sure our smoke detectors are checked and the batteries are changed regularly or dating perishable food items so that—for things sitting in the back of the refrigerator—you know for a fact that they’re two days instead of two weeks old and have gone bad,” Reiter said. “Having a second person smell food before you use it can be a great option too.”

Peter Buckley, M.D., dean of VCU School of Medicine, said the results of the study illustrate the broader impact of COVID-19 infection.

“Over the past year, we’ve played witness to the catastrophic consequences the pandemic has wrought on our nation, and the specter of mental health problems related to COVID-19 is significant. As health care providers, we need to be mindful of the mental health impacts of lingering symptoms, such as the loss of smell and taste, as the survey respondents’ reported symptoms of depression related to lost quality of life could have consequences far beyond this pandemic,” said Buckley, also a professor in the Department of Psychiatry.

“COVID-19 has brought attention to the field of smell loss and its lasting impacts on patients,” Costanzo said. He and Coelho are continuing efforts to develop an implant device to restore sense of smell, much like a cochlear implant restores hearing for those with hearing loss. The project, which they have been working on for several years, has received international interest since the onset of the pandemic as more cases of smell loss arise.

Source: Read Full Article