Researchers at UPF are testing a new non-invasive method of stimulating the vagus nerve in mice that improves their memory. They have shown for the first time that electrostimulation in the ear of intellectual disability rodent models leads to a cognitive improvement. The study is the result of collaboration between research groups at the Department of Experimental and Health Sciences (DCEXS) and the Department of Information and Communication Technologies (DTIC). It has been coordinated by the researcher Andrés Ozaita, principal investigator at the Neuropharmacology Laboratory-NeuroPhar, and is published in the journal Brain Stimulation.

Stimulation of the vagus nerve emerged as a therapy to treat epilepsy or depression that do not respond to drugs, because the ramifications of this nerve carry information to deregulated areas of the brain in both diseases. Some of these regions like the amygdala, prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, are also required for attention and memory. For this reason, the technique has also been found to produce a cognitive improvement. Initially, stimulation was carried out invasively, surgically implanting the device that applies electrical impulses. Subsequently, non-invasive approaches were developed, which stimulate the skin’s surface in areas in which the branches of the nerve pass.

Previous studies had revealed the modulation of memory using invasive and non-invasive approaches in animal models and in humans, but non-invasive transcutaneous—through the skin—approaches had not been tested so far in mouse models.

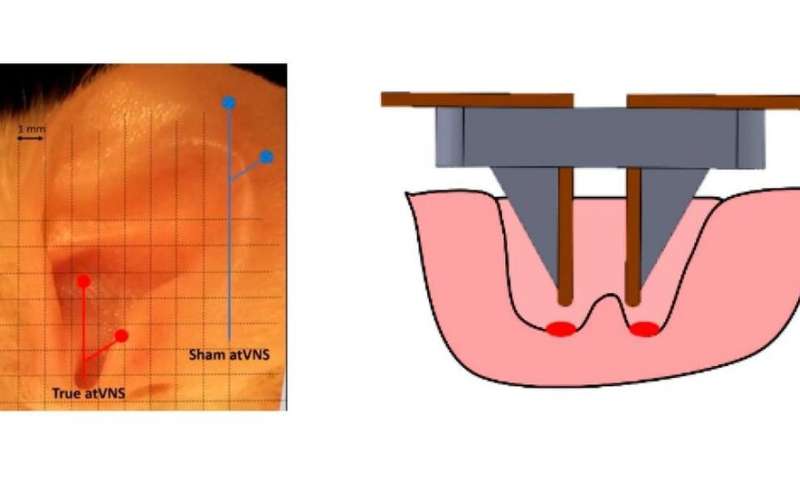

Researchers at the Biomedical Electronics Research Group developed an electrode to allow non-invasive electrostimulation of the vagus nerve in mice. “Mikel Domingo-Gainza, a student of the bachelor’s degree in Biomedical Engineering, built the electrode during his bachelor’s degree final project,” explains Antoni Ivorra, leader of the Biomedical Electronics Research Group (BERG) and DTIC lecturer. The device is applied in an accessible area of the mouse’s ear, which is reached by branches of the vagus nerve.

“We show that this technology achieves a behavioural effect of cognitive enhancement in mice,” explains Anna Vázquez-Oliver, co-first author of the article. “We use a test to evaluate the memory in which we value whether the mouse remembers objects it is familiar with. After electrostimulation, the animals achieved better results in the test, their memory lasted longer,” she adds. This would be the first proof in mice; in rats it had been shown that applying electrostimulation to the ear yielded brain responses—more neurotransmitter activity—but no effect on behaviour had been demonstrated.

They then tested the potential of the protocol in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome, the most common form of inherited intellectual disability, which usually shows poor performance in object recognition memory. Transcutaneous stimulation also improved their memory, which supports its relevance in cognitive modulation in the intellectual disability mice model.

In the words of Cecilia Brambilla-Pisoni, co-first author of the study, “the activity we are generating artificially in the fibres of the vagus nerve would produce an activation of areas of the brain that are important for memory. We hypothesize that an increased release of noradrenaline would occur, making the information better consolidated.”

Source: Read Full Article